Why President Biden Must Make Latin America a Foreign Policy Priority and Fight Kleptocracy and Illicit Trade

Today’s Latin cartels are spreading deadly violence, diversifying their illicit portfolios, expanding illicit economies, and financing greater insecurity and instability

David M. Luna

26 January 2021

President Joe Biden has signaled in recent months that “America is back” and expressed a strong foreign policy commitment during his Inaugural Address to peace, prosperity, and security anchored in dynamic diplomacy and working through alliances, public-private partnerships, and global institutions to address many of today’s global challenges and to restore democracy. President Biden has stated that fighting kleptocracy will be an important part of his national security agenda.

Latin America must be a priority for the Biden administration.

Such a statement of policy would no doubt be a welcomed message across diplomatic circles and communities across Latin America, but especially those working the frontlines to strengthen cross-border cooperation and responses to confront converging threats such as COVID-19, economic recovery, migration, corruption, organized crime, and terrorism.

The Criminal Co-option of the Mexican State

In Mexico, cartels and organized criminals have co-opted the government at the federal, state, and local levels, and have diversified into other sectors such as agriculture, mining, and transportation. Through their corruptive influence, they now control strategic and critical infrastructure such as the country’s major ports. The significant infiltration and penetration of these criminal groups have destabilized Mexican governmental institutions and markets, the rule of law, and regional security.

The battle by cartels in Mexico in recent years over lucrative illicit markets is illustrative of how violence has not only increased across the country and in neighboring states, but also how it has led to the illicit-licit business diversification of Latin cartels into other sectors, threatening our collective security. These sectors include: luxury apparel (counterfeits); food and agriculture (e.g., cattle and fruits/avocados); oil and gas (bunkering); mining (illegal logging, extraction of natural resources); seafood (illegal fishing); alcohol and tobacco (illegal production, smuggling, diversion); and other industries impacted by illicit trade. Today’s global illegal economy accounts for several trillions of dollars and possibly up to 7 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP).

In Mexico, the cartels earn tens of billions of dollars annually from drug trafficking and other criminal activities used to finance greater insecurity. Since 2006, over 200,000 people have lost their lives as a result of the ruthless violence by the cartels in Mexico, with over 40,000 deaths in 2020. In addition to innocent civilians, many hundreds of political leaders at the federal, state, and municipal levels, police officers, soldiers, judges, congressmen, and investigative journalists have been murdered.

The cartels are well-resourced and outfight security forces with their own military-grade equipment and weapons. They also are able to finance their impunity through the strategic use of bribery, corrupting public officials at all levels of government, corroding rule of law institutions, and creating a climate based on fear (“plata o plomo”). As a result, many of the Mexican cartels have grown in strength as they fight for turf and strategic control of trafficking routes along the U.S.-Mexico border for narcotics, human trafficking, weapons, dirty money, and other contraband. Their reach is now global, expanding to other regions of the world particularly Africa, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific.

It is likely that revenue for most cartels declined slightly during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic as supply chains internationally were on lockdown – especially Chinese exports of precursor chemicals to make fentanyl and methamphetamines. But criminal activities have since resumed as seen in the seizures of fentanyl in Mexico, which increased by almost 500 percent in 2020. The Sinaloa cartel, the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG), and other Mexican organized criminal organizations continue to exploit illicit economies to grow their criminal enterprises through new income streams.

The legalization of marijuana, loss of heroin markets to the fentanyl trade, and greater U.S. border enforcement has also led to their entry into other illicit markets. This is of particular concern given that Mexico ranks among the highest criminal markets in Latin America in crimes related to smuggling and piracy including music, footwear, clothing, and other fakes or imitated goods.

Escalating Regional Security Crisis

The coercive impact, intimidation, and control of critical infrastructures, public institutions, and territories are critical to the success of the aggrandizement of cartels’ illicit empires.

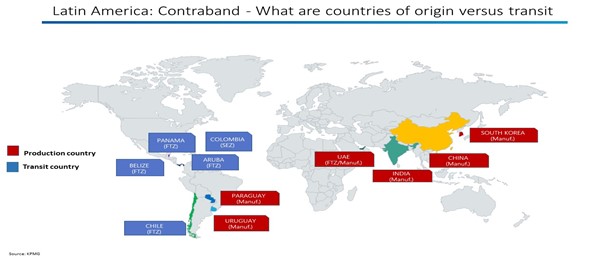

The cartels and other bad actors wield great influence over the largest seaports in Mexico including Lázaro Cárdenas, Manzanillo, and Veracruz, from where they can launch their smuggling operations on an array of counterfeits and other contraband. These strategic assets enable them to move illicit goods across Mexico, into the United States, and beyond. For example, the Cártel del Tabaco, which has numerous business connections with CJNG and Los Zetas and involvement of complicit corrupt officials, has illegally imported illicit whites from China, UAE, India, and other countries, including through the misuse of Free Trade Zones (FTZs) in Panama, Belize, and Paraguay. The Cártel del Tabaco has also started manufacturing their own brands with Mexican-grown tobacco and using violence to force vendors to sell these illegal tobacco products.

The illicit tobacco trade has also impacted American communities. Illicit cigarette consumption in the Americas accounts for 22 percent of the overall market (a loss of $6 billion in revenue) and these illicit tobacco products are largely manufactured and smuggled through FTZs, Paraguay, China, India, UAE, and Korea.

For example, in early 2020, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) seized over 420 million cigarettes that were intended to be smuggled from U.S. to Mexico. The criminal conspiracy involved members of Los Zetas. This was the single largest illicit cigarette seizure ever recorded globally, with a total value estimated at $88 million. FTZs again were instrumental in moving such contraband from the UAE and Panama into McAllen, Texas.

But illicit tobacco is not the only new non-narcotics-related criminal market from which the cartels are profiting.

The avocado, fruit, fish, and meat industries now see the active involvement of the cartels to increase illicit wealth and launder their dirty money. Either through extortion of avocado and fruit farmers or seizing farms in the state of Michoacán, Mexico’s cartels have expanded into the food sector.

Illegal fishing in Baja California and the Pacific Ocean has brought many types of fish close to extinction, including the totoaba which is highly-prized for its swim bladder and sold in black markets in Asia for thousands of dollars for a single fish. Such illicit fishing has also impacted the endangered vaquita. Investigations by Earth League International have found strong Mexican cartel links with criminal syndicates in China who smuggle the totoaba bladders from Mexico and U.S. into Asian black markets. These Mexican-Asian criminal joint ventures, that operate as well in the United States, have also been involved in human smuggling, money laundering, and other illicit trafficking areas.

The oil and gas and mining industries are other sectors that have experienced increased criminal penetration by the Mexican cartels. For years, Mexican cartels have profited by illegal oil bunkering and diverting crude oil from pipelines in the country. They have also engaged in the extortion of iron ore mining and logging companies and kidnapping for ransom of their executives. Recent reports have raised concerns about cartels eyeing the new lithium mining operations in the Sonoran desert, and illegal logging in the mountains of the northwestern state of Chihuahua.

In Colombia, law enforcement communities still remember the violent days of Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cali cartel’s entrepreneurial efforts that build a global empire predicated on the cocaine trade. Colombian cartels have long since diversified into other sectors beyond the diminishing returns from cocaine trafficking, simply supplying the contraband to the Mexican cartels which in turn do the heavy lifting into the United States and other illicit markets. Today, they are involved in illegal mining of gold and other natural resources, extortion, human trafficking, and other smuggling activities. For example, illicit goods and contraband from Asia create numerous lucrative opportunities for Colombian criminals to reap in illicit trade and launder their dirty money, including massive amounts of illicit cigarettes brough through the Colon Free Zone of Panama. Criminal mining of gold and the illegal extraction of minerals and other precious natural resources has become “more lucrative than drug trafficking”.

In Paraguay, and the tri-border in South America, a confluence of bad actors and threat networks export criminality and illicit financial flows through novel trade-based money laundering related to the trafficking of counterfeits, weapons, drugs, electronics and other contraband. Paraguay also accounts for about 11 percent of the global supply of contraband cigarettes. In fact, Hezbollah and other terrorist group sympathizers, continue to finance violence and insecurity throughout the tri-border area and other parts of Latin America. The Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) is heavily involved in the very profitable smuggling trade out of Paraguay including counterfeits and illicit cigarettes used to buy weapons and corrupt officials throughout the country.

In the Northern Triangle of Central America – Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala – corruption and criminal gangs have created some of the most dangerous communities with the highest homicide rates in the world. Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), the Mexican cartels, and other criminal organizations, along with a complicit kleptocratic network of government officials, have unleashed a violent storm of brutality and impunity. The increased trafficking of drugs, arms, humans, and other contraband continues to fuel insecurity that contributes to the migration of families to the United States trying to escape the extreme violence in the region. Those individuals, especially young adults who stay behind, become more desperate and vulnerable to crime and recruitment by organized crime.

Illicit Economies and Misuse of Free Trade Zones (FTZs) by Criminals and Bad Actors

In March 2020, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) underscored how FTZs are “misused for money laundering and terrorist financing” from the proliferation of weapons of mass destructions (WMD) to the trafficking of alcohol, cigarettes, and other high duty items “that are more vulnerable to smuggling and contraband due to the increased revenue that can be generated by not paying tax.” Illicit threats in one jurisdiction have ripple effects that impact many other jurisdictions especially when FTZs, for example, are exploited and misused by criminals and other bad actors, and when goods that “originate from, or [are] trans-shipped, through FTZs [are] not subject to adequate export controls.”

Through the corruptive control of ports and FTZs across the Americas, Asia, and globally, the Latin cartels and other criminal organizations are able to import licit and illicit goods to further expand their international illicit trade and export criminality and violence to other markets. The exploitation of hemispheric cross-border trafficking and smuggling corridors includes illicit hubs in Panama’s Colon Free Trade Zone, Isla Margarita in Venezuela, Maicao Special Customs Zone in Colombia, Ciudad del Este in Paraguay, the Aruba Free Trade Zone, Corozal Free Zone in Belize, and others.

Moreover, criminals and complicit operators in unregulated zones continue to engage in deceptive trade and transshipment practices including fraudulent bills of lading, transactional invoices, and country of origin declarations, as well as mislabeling of goods, manufacturing illicit products, and laundering dirty money in many of these FTZs. Illicit trade across e-commerce has also exploded. According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), much of seizures of infringing goods arriving at U.S. borders is “trafficked through e-commerce” and has increased ten-fold.

Cartels have also been creative in laundering their illicit funds through the formal economy, exploiting some of Mexico’s iconic products such as tequilas and other consumer goods. Trade-based money laundering remains an important method that cartels use to move and clean their dirty money by purchasing luxury goods in the United States in dollars – including footwear, sportwear, electronics, and tobacco products – and exporting such goods for resale to Mexico where the profits are legally integrated into the financial system.

Addressing the growing insecurity spurred by violence and criminality in Mexico and the Americas will be critical in the coming years. In addition to mobilizing whole of society approaches to fight illicit trade, it is important for the private sector to strengthen the political will in Mexico, and across FTZs in the region, to ensure that governments create a climate of transparency and ensure enforcement of laws including those to effectively fight organized crime, corruption, and money laundering.

We also must ensure that such violence and criminality — when coupled with porous borders and entrenched corruption — are not further exploited by terrorist groups that converge into a bigger threat altogether to the detriment of our hemispheric collective security.

Fighting Kleptocracy and Illicit Trade: Partnerships for Enforcement and Economic Security

The recent Model Law to Combat Illicit Trade and Transnational Crime by the Latin America and Caribbean Parliament (Parlatino) can help to materialize the regional political will in the prevention and fight against illicit trade and transnational organized crime including through the participation of both public and private sectors – with the special participation of Latin American citizens – and help countries to meet their sustainable development goals.

The U.S. Congress and the Biden Administration may want to similarly encourage Latin American partners to fight kleptocracy and illicit trade through implementation and enforcement of this important Model Law.

The United States must implement the Corporate Transparency Act that was passed by the U.S. Congress in January 2021 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021. Latin cartels, counterfeiters, and other bad actors continue to exploit U.S. incorporation laws and manipulate the global financial system to launder their criminally-derived profits. Such criminality has real-life consequences that harm our national security, American business interests, as well as the health and safety of citizens especially as the cartels continue to expand their market share across the region’s economies, and online ecommerce platforms.

Furthermore in this COVID-19 pandemic, and with efforts to stimulate economic recovery, Mexico and other countries that are losing precious revenues in the amount of tens of billions of dollars a year to illicit trade must strengthen cooperation across borders to disrupt illicit economies, prosecute corrupt officials and criminals, and confiscate their dirty monies.

As I have stated in numerous diplomatic fora in recent months, the B20/G20, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Organization of American States (OAS), World Customs Organization (WCO), and other diplomatic fora, we must elevate the fight against organized crime and illicit trade.

As Chair of the Business at OECD Anti-Illicit Trade Expert Group (AITEG), we are working to ensure that this important international agenda is one that is shared by partners across sectors including through collaborative public-private partnerships with Colombia, Mexico, and other countries across Latin America, and globally.

Public-private partnerships and collaborations will also be vital to confront the cross-border threats posed by the Mexican cartels and other threat networks in anticipating and addressing these geo-security realities, especially in these turbulent times.

President Biden and his administration are revitalizing alliances to fight kleptocracy and transnational threats including working on a new approach to build security, stability, and prosperity in partnership with Mexico, Central America, and other nations in the region.

To ensure greater success that benefits all nations, the United States must test the political will of Latin leaders to fight corruption and organized crime, enforce their laws, and prosecute kleptocrats and ruthless criminals. It also will be more important than ever to employ whole-of-society approaches between governments, business, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in order to develop sustainable security solutions in the battle against today’s cross-border criminal threats to help ensure safer, more secure communities tomorrow.

David M. Luna, a former US diplomat and national security official, is president and CEO of Luna Global Networks & Convergence Strategies, and currently chair of the Business at OECD AITEG, chair of the Anti-Illicit Trade Committee of the US Council for International Business, Member of The Business 20 (B20/G20) Integrity & Compliance Task Force, and co-director of the Anti-Illicit Trade Institute, Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center (TraCCC), Schar School of Policy & Government, George Mason University.